For all the vehemence that you feel in his work he painted very slowly, with intense, exquisite care, like a man in love. That is indeed what he was—in love, obliviously, with whatever spirit had enthralled his imagination at the time. And when the picture was finished and the vision was gone, he fell into a mood of desolation in which he wanted to die. He was very young.

I tried to scold Hugo out of those moods. I was with him in April just after he had finished his "Loch Corrib"—you know of the innocence, the angelic tranquility in it, like the soul of a child. He would not go near the lake: 'It is nothing to me now,' he said somberly, 'I am done with it.'

'Hugo!' I said laughing, 'You are a vampire! The loch has given you its soul.' He answered, 'Yes: that is true; corpses are ugly things.'

For a month that empty, dead mood lasted and Hugo hated the entire world. I took him to London to give him something to hate. After two days he fled back to his tower and breathed the smell of the peat and sea-wind, and the sweet home-welcome of burning turf, and he looked out on Ireland with eyes of love. The next morning, he came in from a bath in the loch with the awakened, wondering look I had long to see and said, 'I am going to paint Roisin Dhu.' He then went off to walk the west of Ireland seeking a woman for his need.

I was astonished and excited beyond words; he had been so contemptuous of human subjects, although I remembered, in his student days, studies for heads and hands that made one artist whisper 'Leonardo!' under his breath.

I wondered what woman he would bring home.

They came about two weeks later, after dark, rowing over the loch, Hugo and the girl alone.

After supper, sitting over the turf fire in the round hall of the tower, Hugo told me that she was the daughter of a king.

She smiled at him, knowing that he spoke of her, although she didn't speak English. I told her Gaelic what he had said. She answered gravely, 'It is true.'

I looked at her, then she moved from the window to her chair, and I felt almost afraid—her beauty was so delicate and so remote...

"Those red lips with all their mournful pride'... Poems of Yeats were haunting me while I looked at her. But it was the beauty of one asleep, unaware of life or of sorrow, or of love... The face of a woman whose light is hidden.

She sat in the shadowed corner, brooding, while Hugo talked. He was at his happiest, overflowing with childish delight in his achievement with eagerness for tomorrow's sun.

Nuala was her name. The King of the Blasket Isles was her father—a superstitious, tyrannical old man. Hugo had been able to make no way with him or his sons.

'I invited one of them to come, too, and take care of her,' he said, 'but they would not hear of it at all.'

'The old man was as dignified as a Spanish Grandee.'

'"It is not that I would be misdoubting you, honest man," he said, "but my daughter is my daughter and there Is no call for her to be going abroad to the world."

'And her brothers were just as obstinate:

'"It is not good to be put in a picture: it takes from you," they said.'

'They got me into a boat by a ruse, rowed me "back to Ireland", and when they had landed me, pulled off.

'"The blessing of God on your far traveling!" they called to me gravely: a hint that I would not be welcome to the island again.

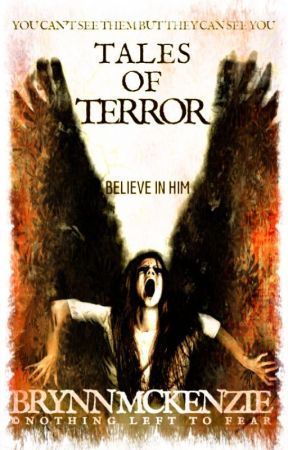

YOU ARE READING

TALES OF TERROR

Short StoryTALES OF TERROR *CreepyPastas *Urban Legends *Ghost Stories

Portrait of Roisin Dhu

Start from the beginning